The Bomber Jacket from First Page to Finally, Published!

Exploring History

On May 5, 2004, almost seven years to the day we left for our first Scotland trip, Dana and I began our second journey to Scotland. It was on this amazing 26-day adventure that the well filled to overflowing and a story idea, characters and setting began to bubble up. Though my photos, mementos and typed notes from my travel journal fill two huge scrapbooks, this blog will focus on places that most influenced the atmosphere of The Bomber Jacket or became locations in the novel. Much of the wording and many of the descriptions in this blog are taken directly from my travel journal and have ended up almost verbatim in The Bomber Jacket.

Even now, twenty years later, I can hardly believe we found the time and money for this trip. Although I had the accumulated vacation days, I don’t know how I got permission to take them all at once. And Dana unfortunately had lots of time—his employer had just laid him off. A few evenings later we watched the movie, The DaVinci Code, whose final scene is set at Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland. We broke out a bottle of scotch, started reminiscing about our 1997 trip, and the next thing we knew, we’d booked a flight! (Seems my decision to travel is very influenced by movies.)

This time we flew Aer Lingus from BWI to Edinburgh, via Dublin. We had the beginning and end of our trip booked: two days in Edinburgh to start and two days in Dublin to finish, several destinations in mind, but no set agenda. We planned just to wander at will.

Once again, but in much better weather than 1997, we explored Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, bookended by the imposing Edinburgh Castle high atop castle rock, and Holyrood Palace and Abbey a mile down the descending road. To my great delight, in a small alley (called a close in Scots) we discovered The Writers’ Museum in a charming tutor-style building honoring Scotland’s writers: Robbie Burns (Auld Lange Syne), Robert Louis Stevenson (Treasure Island), Sir Walter Scott (Ivanhoe, Rob Roy), to name a few.

I meandered through the ruins of Holyrood Abbey, built in the 12th Century. The morning, which had started gray and threatening, had turned to a brilliant cobalt blue. Wispy white clouds floated across the narrow expanses of the empty arched windows which formed natural frames for the tall, green trees in the nearby garden. As I stood at the tomb of James V of Scotland—the father of Mary, Queen of Scots–who died in 1542, I was struck by a sensation of being pulled out of time. It was a feeling I experienced repeatedly on our unhurried exploration of this fascinating land.

On a walk through the colorful Princes Street Gardens, which lie in a hollow below the castle, I sat on a bench inscribed “To the citizens of Edinburgh in appreciation for their warm hospitality. Presented by the officers and airmen of the USAF at RAF Kirknewton, March 1962.” Looking across the wide expanse of green with trees of all kinds, the traffic behind me melting away, I imagined lovers on May 10, 1940 wandering arm-in-arm, unaware that the war with Germany was about to take a drastic turn that day as Hitler’s forces invaded the Netherlands.

Indeed, the well of my imagination was filling up.

Leaving Edinburgh, we headed 24 miles east to the Museum of Flight, located on the former aerodrome (airbase) of East Fortune. I’d hoped there would be more remnants of the airbase, but only a few barracks and a hangar remained. It was a dank, drizzly day, befitting the mood of the deserted airbase. You could almost smell the fuel oil and hear the echoes of throbbing engines against the vacant, blue-doored cement barracks. Fighter squadrons were stationed here and a few miles away at Drem from 1942-1945 to protect southeastern Scotland.

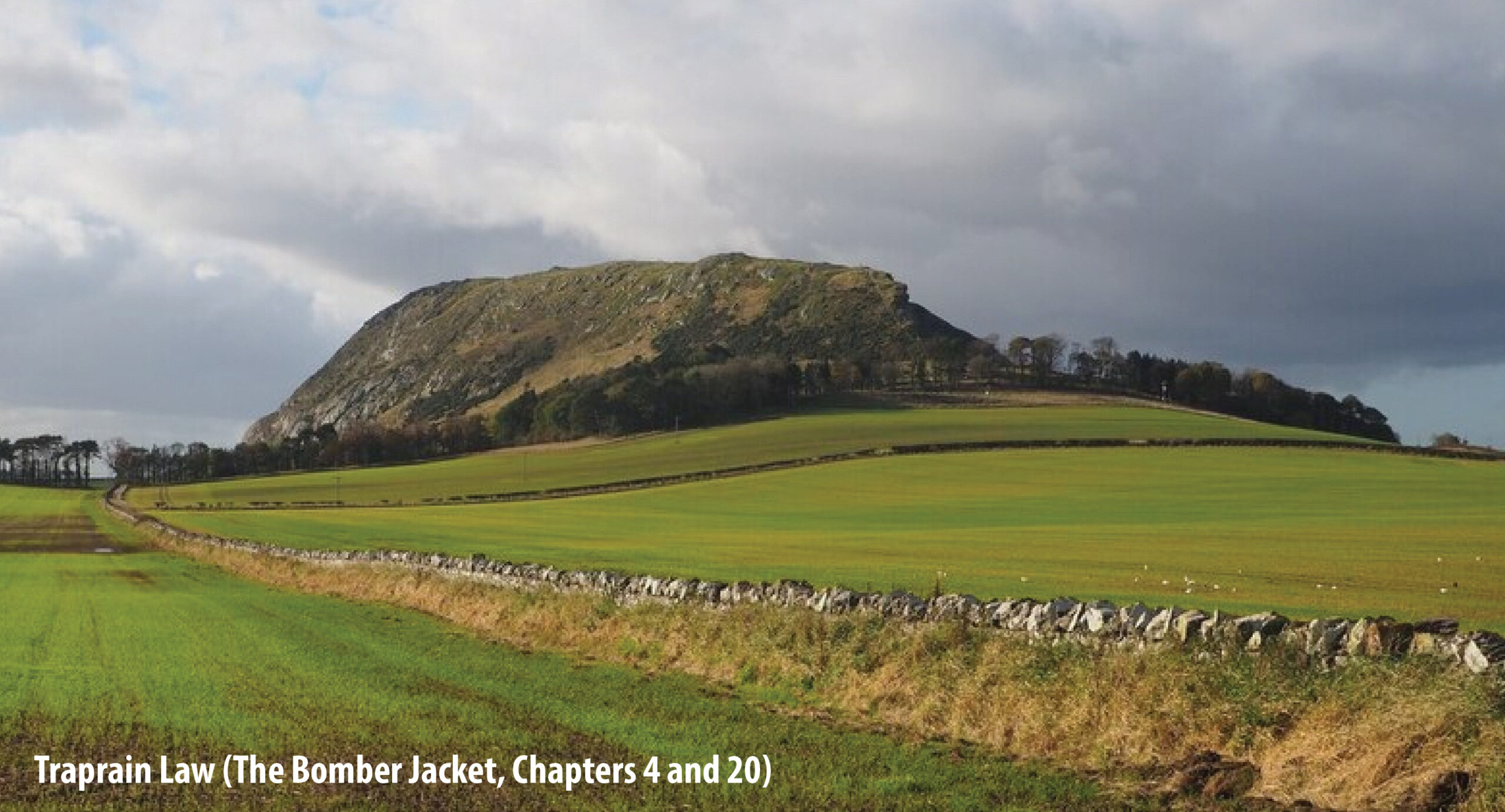

One of the guides, Charlie Carruthers, whose thick brogue required careful listening, told us “the war started and finished here” in this area of Scotland. The first German plane shot down over Britain during the war was downed by a fighter from Drem. On that same day, two land mines were dropped on nearby Traprain Law, an ancient volcanic outcropping which we climbed the next day.

Charlie told us of being an eight-year-old boy hiding in the cellar with his aunt in the nearby village of Haddington on that day as it was bombed by the Germans. Haddington housed a number of RAF officers who were stationed at Drem and East Fortune during the war.

He said the last battle of the war also took place in the Firth of Forth (a bay leading into Edinburgh). Apparently, a German U-boat got through the antisubmarine netting at the mouth of the Firth and surfaced after the cease fire agreement had been signed and sent out. His radio was nonoperative and he didn’t realize that Germany had surrendered. When the boat surfaced, it fired off a volley of torpedoes and the locals thought it was fireworks celebrating the end of the war.

One of the most haunting places in the area was Trapain Law. By the end of the exhausting thirty minute climb my feet were damp and Dana’s pants were marked with mud, but we were rewarded with a stunning 360-degree view of the countryside. How do you capture in words the intense green fields that lay like a crazy quilt below the huge hill or veils of misty clouds that come sweeping across the plains to the top of the hill, so close you could reach up and grab a piece. Everything was reduced to three colors: emerald green, earth brown and mist gray.

Jackdaws, green woodpeckers, wrens, finches, crows surrounded us with song. Standing on that eerie promontory on that gray, misty day helped me understand why ancient peoples felt mountains were dwellings of the gods. I looked into a small pool of rainwater, hoping to see in the reflection “some things that were, some things that are, some things that might be,” as Galadriel told Frodo in the Lord of the Rings. But all I saw was moss and reeds and rocks.

Before we left the area known as East Lothian, we spent some time in the pretty market town of Haddington, Charlie Carruthers hometown.

The last place we visited that directly related to World War II was the island of Orkney, 336 miles north of Edinburgh. Orkney is actually a group of 70 islands; 17 are inhabited. During WWII Orkney hosted four airbases and a Royal Naval Station. The harbor of Scapa Flow was the British fleet’s home port, as Orkney was believed to be out of reach of German U-boats. But in 1939 one snuck into the harbor and sank the HMS Royal Oak. It still rests at the bottom of the bay, a watery grave for hundreds of its crew, including 134 boy seamen, not yet 18 years old.

In a place where thousands of men and women, airplanes, ships, barracks, airfield and the equipment of war existed, now only two buildings remain. Time has rusted or crumbled away what man created for war. Across the bay are the Stenness Standing Stones, more than 5,000 years old, silent witnesses to the passage of time and the brevity of life.

Though still standing is the tiny exquisite Italian Chapel, built by Italian POWs in a corrugated iron hut in the midst of their POW camp.

In all, we traveled 1,541 miles from one end of Scotland to the other and back. When I returned home to Pennsylvania, a story began to spill out onto the page.