The Bomber Jacket from First Page to Finally, Published!

Writing historical fiction is a LOT of work, especially if you want to get the history part right. And having a degree in history education made accuracy even more important to me. Writing fiction set in World War II has its own set of challenges. On the plus side, there’s an enormous amount of material about the time period in every media imaginable. On the negative side, there’s an enormous amount of material about the time period in every media imaginable.

Even though it’s fiction, if you’re writing about World War II, you’d better believe there will be readers who know if you get important details wrong. And that ruins your credibility. On the other hand, as I delved into the research process, I had to constantly remind myself this was historical fiction, not a history book.

As I was developing my characters and their backstories, I was also doing research about not just the war, but also the lives and times of those who lived through it in Scotland. How did people dress? What did they eat? What was their house or flat like? What kind of work did they do? What was day-to-day life like in the capital city of Scotland and on a remote estate in the highlands? How did they cope with the death and destruction that rained down on Britain, not just in England but in industrial cities in Scotland? How did they have the courage to endure, let alone go into battle on land, sea, and air?

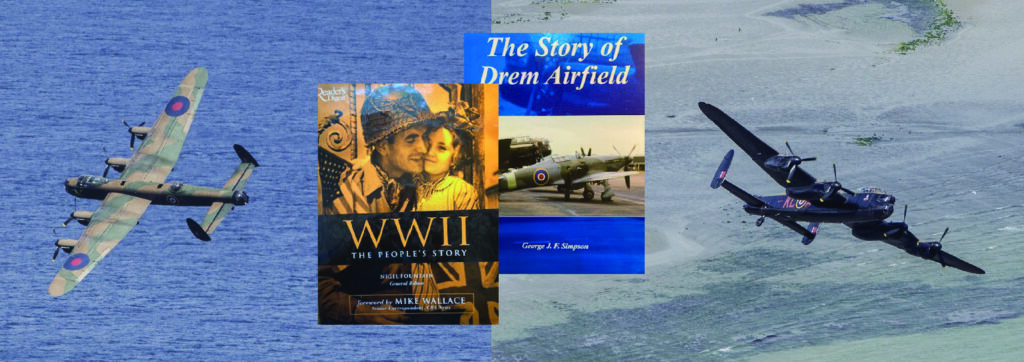

Sometimes I would spend months reading detailed histories, delving into documentaries, exploring websites with personal stories, watching WWII movies, and immersing myself in World War II fiction. I’ve long since forgotten the names of the many books and reference materials I read, but I still have four of them on my bookshelf: The Story of Drem Airfield, a 72-page booklet by George J. E. Simpson, which I had purchased there in 2004; an oversized photo-filled book published by Readers Digest: WWII: The People’s Story; two volumes of This Fabulous Century by Time/Life Books: 1930-40 and 1940-50.

My bomber pilot was a member of the British Royal Air Force, assigned to Bomber Command, so there were an uncountable number of small details I needed to understand and incorporate into my story: the difference between Stirling and Lancaster bombers; how many crew members served on a Lancaster and each member’s role; how crews were assigned; the basics of flying a bomber; life on a Scottish airfield. Just to begin with.

During that research I learned that approximately 125,000 men flew on missions for the RAF Bomber Command, most in their late teens and early twenties. Of them, 55,573 did not survive. That’s a 44% fatality rate. Only one in six newly-minted crew members was expected to survive their first tour of duty, consisting of 30 missions.

Those are stunning and sobering statistics and made it important to capture the experiences, state of mind and personal life of Colin, my bomber pilot. I was incredibly fortunate to learn about that experience from Richard Boyd, a decorated RAF bomber pilot, who not only flew missions, but trained American and Canadian crew here in the States and Canada. Some years after the war, he settled in the United States with the Canadian girl he met during the war.

For several years I attended the World War II weekend sponsored by the Mid Atlantic Air Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania. There I talked to living history reenactors, attended lectures, wandered around encampments, looked at famous airplanes inside and out, including one year, the only still airborne Lancaster Bomber in the Americas.

In 2010, I could have taken a 10-minute ride in that Lancaster Bomber for $400. Because $400 was a lot of money, I didn’t. I really regretted that decision later as I tried to imagine and convey the experience of taking off, flying and landing in that huge, loud, lumbering aircraft.

Two people I did not have the fortune of discussing life during WWII were my own parents. Growing up, my father, who was in the army in Europe, never talked about his experiences. My mother only occasionally shared stories of difficult times being a mother of a young child with a husband overseas. By the time I started writing The Bomber Jacket in 2005, both my parents were gone, my mother in 1992 and my father in 1997. All the questions I then longed to ask them, I had failed to do so while they were living.

Recently I chatted with some of my siblings about the little our father told us when one of us would probe. When we put his spare answers together, we determined he was a radio operator assigned to an artillery unit that saw action in Sicily and the Italian campaign, and was in Belgiuim and the Normandy region of France in the later part of the war. Our uncle claims our dad was a driver for some “high up mucky-muck” in Paris. We know he was on a ship bound for the invasion of Japan when the war ended. And that he sold all of his gear to buy beer and play poker. He told my husband he didn’t understand how he lived through the war. And he refused ever to stand in line again for anything for the rest of his life.

When you are young, you don’t think about your parents’ experiences. They are lost in the murkiness of “the past,” which for a kid is irrelevant. I loved history growing up, but never expected to write a story set in WWII about contemporaries of my parents. So my advice to anyone with living parents and/or grandparents: ask them for lots of stories of their life. Beg them to write a memoir, make recordings, or sit and talk to you as you take notes.

Don’t let your own family’s history fade into the past.