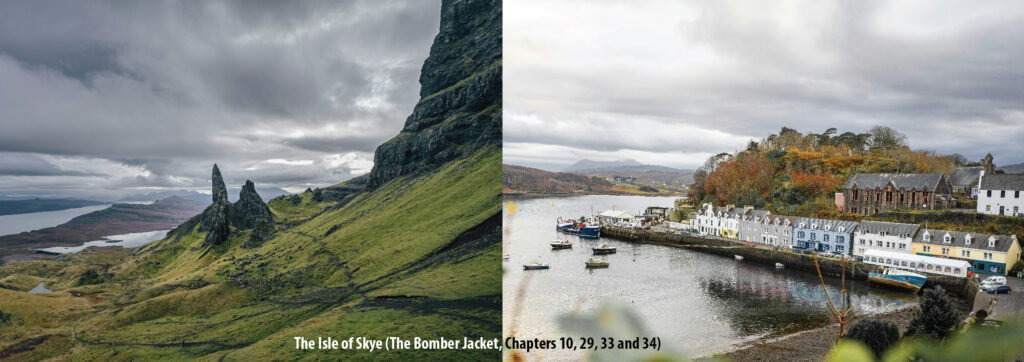

The Bomber Jacket from First Page to Finally, Published!

A First Editor and Endless Rewrites

Every writer who wants to put their story out into the world knows that getting feedback is part of the process. At first this typically involves joining a writing group consisting of other people also penning their first novel, or short story, or series of essays. Or you might share your novel in progress with close friends and family members, asking them to tell you “What do you think?

However, it can be difficult for a writer to take feedback graciously, even gently crafted critiques. Although there’s controversy about who penned the famous quote: “Writing is easy. You just open a vein and bleed,” it’s true that when you write authentically, you “bleed” onto the page and thus are “wounded” by the end of your first draft. To then eagerly ask others to pour salt on your wound by giving their take on your plot, use of language, character development, and exhausting efforts to bring your story to life, requires that you develop skin as thick as a turtle’s. And to even act a bit like a turtle and withdraw inside your shell and chew on the advice for awhile before you react to it.

Yet detailed feedback on your novel is priceless, be it from a committed writing group invested in giving both encouraging and pointed critiques of your story or a professional editor who works with you on developmental and line editing. For clarification, a developmental editor concentrates on the story itself: how the plot unfolds, the way characters manifest what motivates them, the sequence and pacing of scenes, and how the entire story fits together. The line editor focuses on your writing style, sentence structure, word choice, grammar, and fact checking. This is much different from the “Oh I loved it,” you get from your besties and siblings.

After the second draft of The Bomber Jacket was done, it was time to take a deep dive into the novel and I needed a trained, skilled, and neutral eye to help me. Dani Church was not just a family friend (she and my youngest sister had been best friends from early elementary school), but also a talented fiction writer, exceptional developmental editor, and accomplished line editor. And she didn’t pull any punches in telling me where my story started sagging, ways in which my writing was confusing, and what to do to increase the tension in a scene.

With her help, I learned to watch for point of view errors. “Her cheeks were bright from the crisp air, her hazel eyes were snapping, her pony tail bobbed,” I wrote. Dani’s response: “You’re writing from Beth’s POV, so she would not notice how she looks, unless she pauses inside the front door at a mirror to admire her new purchase. Or perhaps she sees her reflection in the glass of the door as she approaches the house? Otherwise, an edit is necessary. I’ll do it here to help out…show you what I mean. Another option: fit her description in when she’s trying on the jacket, looking at herself in a mirror.” And she offered a suggested rewrite.

She pointed out instances of “lazy writing:” For example, I used the phrase, “with an agitated look” and she remarked in the edits: “What’s an “agitated look?” Use a description, rather than reply on one word.”

She picked up on repeated words in a paragraph or a page or adjacent pages and suggested alternates: “On the second Sunday of November, there was a guest preacher at their church— the First Presbyterian Church of Carlisle—a visiting minister from the Church of Scotland, which Beth knew was the predecessor of the American Presbyterian Church.“ Dani directed me to “Try to cut this down, tighten it up. Too many church references all thrown together. It’s like a bump in the road while reading.”

She was constantly helping me tighten up my prose in small, but effective ways:

Beth stood up, excited by her idea. “Yeah, that’s what I’ll do! I’ll go into school tTommorow I’ll andask my counselor see if there’s any way I can change schools.

“That’s not like you to be so impulsive.” Her grandfather was frowingfrowned at her in the oddest way.

“I’m getting a bit bored,” Dani said when we reached Chapter Nine. “You need some conflict here. Something to come between Beth and Robbie. Something to make their relationship more complicated.” And thus was born the Canadian student, Iain Fraiser, who stuns Beth by being interested in her.

Dani made comments that totally changed how I wrote certain scenes: “This is HUGE! And so wasted telling it as a past recollection. It has totally lost its punch. I recommend doing a rewrite that puts us in a more linear timeline as Beth goes off on this journey of discovery. I, as a reader, want to discover these things along with her, not read about them as she remembers doing them.”

She was clear about her reaction to the conclusion of the novel: “I’m not content with this quick wrap-up. I want to hear some of Henry’s explanation … but not at the very, very end.”

Because of those last two pieces of vital professional critique, I completely rewrote the ending of the book, adding two chapters and intertwining the time lines of 1944/1945 with 1997. That meant in mid-2016, after a year of intense editing, my third draft was finished. And so much better for it.

But I wasn’t done. It needed more work. In the fourth draft, I completely cut the first two chapters. Much as I loved them, they bogged down the book’s beginning with backstory. I realized I could weave important pieces of that backstory into the story throughout the book.

At last, by the end of 2016, I was ready to begin that most painful of processes: the search for an agent.